Es ist kaum zu glauben, aber wahr: „Die Rente ist sicher!“ war der Slogan im Wahlkampf 1986. Der damalige Bundesarbeitsminister Norbert Blüm hat diesen Spruch geprägt. Die Älteren unter uns werden sich noch daran erinnern.

Vielleicht war Norbert Blüm wirklich davon überzeugt, dass dem so ist. 2024 sieht es jedoch vollkommen anders aus. Doch nicht nur er war dieser irrigen Ansicht. Schon Konrad Adenauer hat bei der Entwicklung und Fortführung der alten „Bismarck’schen“ Rentenordnung so manche falsche Schlussfolgerung getroffen: Vor fast 70 Jahren stellte der damalige Bundeskanzler in der anstehenden Rentenreform 1957 mutmaßlich fest, „Kinder kriegen die Leute immer“. Für die nächsten Jahre sollte er recht behalten. 1964 wurden mit Abstand die meisten Kinder in Deutschland geboren. Aber danach ging es rapide bergab. Der „Pillenknick“ forderte seinen Tribut, und es setzte eine Tendenz ein, die bis in die Gegenwart anhält. Eine Änderung ist nicht in Sicht. Deshalb liegen die Fakten eigentlich auf dem Tisch. Das ist auch kein Buch mit sieben Siegeln oder Rentenhexerei, sondern ganz einfach Mathematik. Das „kleine Einmaleins“ sollte man allerdings schon beherrschen, wenn es um die Ausrichtung der Rente für die Zukunft geht. Beginnen wir aber einfach mal mit den Fakten.

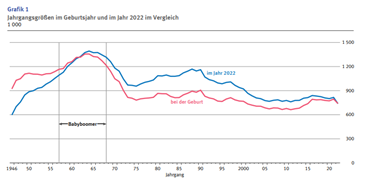

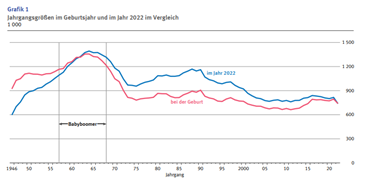

Wie aus der folgenden Grafik ersichtlich ist, sind die Geburten in den vergangenen 60 Jahren drastisch zurückgegangen. Wurden 1964 noch 1,36 Mill. Kinder in Deutschland geboren, waren es 2023 nur noch rund 693 000. Ein Rückgang also um mehr als 50 Prozent. Das hat dramatische Folgen. Bei der Rentenversicherung besteht eben nicht das Kapitaldeckungsverfahren wie bei Versicherungen, sondern das Umlageverfahren. Das heißt: Die jetzigen Generationen zahlen mit ihren Rentenbeiträgen in der Gegenwart das Geld ein, was die ältere Generation an Renten erhält und heute verlebt. Der Staat leitet das Geld nur um, von den Beitragszahlern an die Rentenbezieher. Von den Beitragszahlern gibt es aber immer weniger. Wer nicht da ist, ist nicht auf dem Arbeitsmarkt und zahlt auch keine Beiträge. Die erste Feststellung ist also, es werden weniger Menschen geboren, die 25 oder 30 Jahre später auch nichts einzahlen können. So weit, so gut, aber wie sieht es mit den derzeitigen und vor allem zukünftigen Rentenbeziehern aus?

Die Babyboomer: auf dem Gipfel der demografischen Welle. Quelle: (Statistisches Bundesamt (destatis.de)

Ein weiterer Faktor liegt in der immer älter werdenden Bevölkerung.

„Hatten Jungen bei Geburt um das Jahr 1950 in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland noch durchschnittlich 64,6 Lebensjahre zu erwarten, waren es um 2020 hierzulande bereits 78,5 Jahre. Bei den Mädchen stieg die Lebenserwartung im selben Zeitraum von 68,5 Jahren auf 83,4 Jahre.“

Quelle: Statistisches Bundesamt (destatis.de)

Damit steigt konsequenterweise auch die durchschnittliche Rentenbezugsdauer an. In der logischen Konsequenz entwickelt sich deshalb auch der nächste Faktor negativ. Der Aufwand für die Rente steigt und es gibt mehr Rentner, die länger und gegebenenfalls auch höhere Rente beziehen. Die interaktive Graphik gibt die Zunahme der älteren Bevölkerungsgruppen wunderbar wieder. Es gibt immer mehr Menschen, die älter werden. Dadurch gerät das System langsam aus dem Gleichgewicht. Denn wenn weniger Menschen einzahlen und die Anzahl der Rentner steigt oder länger Rente bezieht, entsteht ein Ungleichgewicht.

Dazu kommt, dass gesellschaftlich und politisch gewollte „Geschenke“ an Bevölkerungsgruppen vorgenommen werden, die nie oder in geringerem Maße in die Rentenversicherungen eingezahlt haben. Auch die Mütterrente für die Kindererziehungszeiten gehören in diese Rubrik.

All diese Entwicklungen führen dazu, dass das Delta zwischen Einnahmen und Ausgaben der Deutschen Rentenversicherung immer größer wird. Da das Geld irgendwo herkommen muss, steigt der Zuschuss des Bundes aus Steuermitteln jährlich an: Betrug dieser im Jahr 1999, also vor 25 Jahren noch 42,53 Milliarden. €, waren es im Jahr 2024 schon über 100 Milliarden Euro aus dem Bundeshaushalt – rund ein Verteil der gesamten Staatsausgaben. Diese Entwicklung ist auf lange Sicht nicht mehr finanzierbar.

Also gibt es – theoretisch – eine Reihe von Möglichkeiten. Alle dürften gleichermaßen unpopulär sein, Politiker scheuen diese Maßnahmen, weil sie die eigene Wiederwahl gefährden, unabhängig von der Richtigkeit der Entscheidung.

Wenn wir uns dem Thema ernsthaft widmen, reicht eine Entscheidung nicht aus. Am wirksamsten wäre ein Mix aus allen Maßnahmen. Die Quintessenz aus diesen Feststellungen ist aber auch eine andere: Private Vorsorge ist erforderlich! Am besten durch eine erfolgreiche und ganzheitliche Kundenberatung wie der privaten Anlageberatung oder einem durchdachten Estate Planning. Je früher, desto besser. Damit aus einem Märchen kein Alptraum wird und das Erwachen für weite Teile der Bevölkerung eine böse Überraschung mit sich bringt.