The question of the existence of a greenium is not only a philosophical one, but also one that concerns many stakeholders in the field of sustainable finance and investment. The question is whether the pricing of green financial products, such as green bonds, should in some way provide a financial advantage. Such an advantage, also called greenium, could exist for various reasons compared to the pricing of conventional bonds. However, the criteria are not as obvious as one might think, as the good (!) cause does not always justify the means.

From a psychological point of view, the answer to the search for a justification for a greenium is quite clear. All parties involved – and here we should mention the issuers as the party seeking capital and the investors as the party providing capital – expect a “reward” for their sustainable endeavours. However, the interests of these groups could not be more different.

The reward for issuers comes in the form of lower financing costs (i.e. a “lower-yield” at the time of issue) and for investors in the form of higher returns (i.e. a “higher yield”). Inefficient capital markets, this dilemma is resolved by balancing the interests in pricing. So, from a “reward” point of view, should the actual yield not correspond to an equilibrium price that is close to the yield on comparable conventional bonds, which would remove the basis for a greenium?

From an economic perspective, the question of a greenium is different. Structurally, green financial products are generally similar to their conventional counterparts, but with small but subtle differences. Green bonds are comparable to conventional bonds in terms of seniority, default risk and rating. However, green bonds have a “green” purpose, whereas conventional bonds are typically used for general corporate financing purposes. [1]. Does this special purpose therefore justify a preferential treatment, a different approach to pricing? It must be taken into consideration that it is not entirely clear whether the green bond was causal in achieving the “green” purpose or whether it could not also have been achieved using conventional financial instruments.

Researchers have been looking into the phenomenon of the greenium for some time now and have come to some very interesting conclusions, particularly with regard to pricing criteria, which could provide important impetus for practical applications. However, the research results are also mixed. Depending on the study in question, there is a cost advantage (greenium) of 0 to 19 bp on the issuer side (!). For example, the Caramichael/Rapp (2022) [2] study by the US Fed shows a cost advantage of approx. 8 bp at the time of issue, but only for the period from 2019 and only for green bonds denominated in EUR and USD.

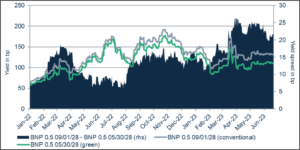

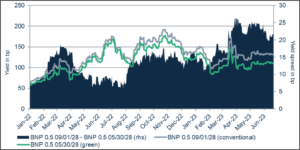

A comparison of the yield of a green bond (FR0014006NI7) and a conventional bond (FR0013532280) from BNP Paribas with a five-year residual term and the same coupon can also serve as an illustrative practical example (see figure below).

Figure 1: Returns of comparable conventional and green bonds based on the example of BNP Paribas (Source: Bloomberg, LBBW Research)

However, research on the issuance of green bonds over the past decade also shows that the green purpose of the financing (often in the energy, transport and real estate sectors) does not actually have an impact on the potential greenium. This is somewhat surprising and contrary to expectations. So what influences the greenium on the issuer and investor side?

On the issuer side, the following are the most prominent factors:

On the investor side, the reasons for a greenium are more nuanced. In particular, the reasons for higher returns have not yet been clearly identified in research. At present, the reasons given are mainly indirect and not necessarily financial in nature. The argument is that while investors are willing to accept lower yields on green bonds in the short term, the environmental and social benefits will only become apparent in the medium to long term, as they are difficult to quantify.

Risk determines the price of a capital market product. Investors primarily look at the yield, spread, or absolute criteria such as financial ratings. “In our experience, investors like green financial products, especially if they help to meet internal targets. However, if you look at comparable green and conventional bonds, there is currently a greenium of 1 to 3 basis points, depending on the product and term to maturity,” says Patrick Steeg, Head of Asset & Liability Management at LBBW.

The noticeable but modest cost advantage (greenium) on the issuer side should be viewed positively, as it may provide an additional incentive to invest in sustainable projects. However, issuers should not be overly optimistic. The higher issuing and compliance costs (certification, reporting) of a green bond must be offset in the final calculation. Only then can an overall assessment be made as to whether the break-even point has been reached or, in the best case, even exceeded.

As the requirements for green financial products become more and more stringent, issuance and compliance costs continue to rise, while the greenium remains at a low level. This raises the question of why the higher costs have so far been borne mainly by the issuers. In any case, Patrick Steeg is optimistic about the future. “With a higher yield curve and decompression of spreads across the entire capital structure, the benefits should increase,” he predicts.

The classic “signalling theory” is celebrating a renaissance, and that is a good thing. Companies that issue green bonds signal to the outside world that they are striving for sustainable business practices, and this signal cannot be measured in monetary units alone.

Co-authors:

Andreas Wein is Head of Funding & Debt Investor Relations at the Landesbank Baden-Württemberg (LBBW).

Simone Reder (LBBW) and Dr. Patrik Buchmüller (Lecturer Risk Manager Non-Financial Risks, FS).

——————————————————————————————————————————

[1] For “green finance” in the context of the green agenda at European Union level and the associated regulatory implications, please refer to Buchmüller/Hofinger (2023). “Bankaufsichtliche Vorgaben zu Nachhaltigkeit/ESG-Risiken” (Banking regulations on sustainability/ESG risks) in: Luz/Neus/Schaber ua (eds.), KWG and CRR, Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag, 4th edition, June 2023. We will publish an update commenting on the new MaRisk as well as the European legal developments, including the EU Green Bond Regulation, EU Taxonomy, CSRD/EFRS and ESG Rating Regulation as a working paper on the Munich Business School website in autumn 2023.

[2] Caramichael, John and Andreas Rapp (2022). “The Green Corporate Bond Issuance Premium,” International Finance Discussion Papers 1346. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2022.1346.

[3] Green Bond Principles (GBP), ICMA, June 2021

[4] Legislative proposal for a European Green Bond Standard (EUGBS), July 2021. Political agreement February 2023